Introduce Static Analysis in the Process, Don’t Just Search for Bugs With It

This article is an authorized translation of my post in Russian. The translation was made with the kind help of the guys from PVS-Studio.

What encouraged me to write this article is a considerable quantity of materials on static analysis, which recently has been increasingly coming up. Firstly, this is a blog of PVS-Studio, which actively promotes itself posting reviews of errors found by their tool in open source projects. PVS-Studio has recently implemented Java support, and, of course, developers from IntelliJ IDEA, whose built-in analyzer is probably the most advanced for Java today, could not stay away.

When reading these reviews, I get a feeling that we are talking about a magic elixir: click the button, and here it is — the list of defects right in front of your eyes. It seems that as analyzers get more advanced, more and more bugs will be found, and products, scanned by these robots, will become better and better without any effort on our part.

But there are no magic elixirs. I would like to talk about what is usually not spoken in posts like: what analyzers are not able to do, what’s their real part and place in the process of software delivery, and how to implement the analysis properly.

What Static Analyzers Will Never Be Able to Do

What is the analysis of source code from the practical point of view? We take the source files and get some information about the system quality in a short time (much shorter than a tests run). Principal and mathematically insurmountable limitations are that this way we can answer only a very limited subset of questions about the analyzed system.

The most famous example of a task not solvable using static analysis is a halting problem: this is a theorem, which proves that one cannot work out a general algorithm which would define whether a program with a given source code will loop forever or be completed for the final time. The extension of this theorem is Rice’s theorem, asserting that for any non-trivial property of computable functions, the question of determination of whether a given program calculates a function with this property is an algorithmically unsolvable task. For example, you cannot write an analyzer, which determines based on source code if the analyzed program is an implementation of a specific algorithm, say, one that computes squaring an integer number.

Thus, the functionality of static analyzers has insurmountable limitations. Static analyzer will never be able to detect all the cases of, for example, null pointer exception bugs in languages without the void safety. Or detect all the occurrences of «attribute not found» in dynamically typed languages. All that the most perfect static analyzer can do is to catch particular cases. The number of them among all possible problems with your source code, without exaggeration, is a drop in the ocean.

Static Analysis Is Not a Search for Bugs

Here is a conclusion that follows from the above statement: static analysis is not the way to decrease the number of defects in a program. I would venture to claim the following: being first applied to your project, it will find unusual places in the code, but most likely will not find any defects that affect the quality of your program.

Examples of defects automatically found by analyzers are impressive, but we should not forget that these examples were found by scanning a huge set of code bases against the set of relatively simple rules. In the same way hackers, having the opportunity to try several simple passwords on a large number of accounts, eventually find the accounts with a simple password.

Does this mean that it is not necessary to apply static analysis? Of course not! It should be applied for the same reason you might want to verify every new password in the stop-list of non-secure passwords.

Static Analysis Is More Than a Search for Bugs

In fact, the tasks that can be solved by the analysis in practice are much wider. Because generally speaking, static analysis represents any check of source code, carried out before running it. Here are some things you can do:

-

A check of the coding style in the broadest sense of this word. It includes both a check of formatting and a search of empty/unnecessary parentheses usage, the setting of threshold values for metrics such as a number of lines/cyclomatic complexity of a method and so on — all things that complicate the readability and maintainability of code. In Java, Checkstyle represents a tool with such functionality, in Python —

flake8. Such programs are usually called linters. -

Not just executable code can be analyzed. Resources like JSON, YAML, XML, and

.propertiesfiles can (and must!) be automatically checked for validity. The reason for it is that it’s better to find out the fact that, say, the JSON structure is broken because of the unpaired quotes at the early stage of the automated check of a pull request than during tests execution or in run time, isn’t it? There are some relevant tools, for example, YAMLlint, JSONLint andxmllint. -

Compilation (or parsing for dynamic programming languages) is also a kind of static analysis. Usually, compilers can issue warnings that signal problems with the quality of the source code, and they should not be ignored.

-

Sometimes compilation is applied not only to executable code. For example, if you have documentation in the AsciiDoctor format, then in the process of compiling it into HTML/PDF, the AsciiDoctor (Maven plugin) can issue warnings, for example, on broken internal links. This is a significant reason not to accept a pull request with documentation changes.

-

Spell checking is also a kind of static analysis. The aspell utility is able to check spelling not only in the documentation, but also in the source code of programs (comments and literals) in various programming languages including C/C++, Java and Python. Spelling errors in the user interface or documentation are also a defect!

-

Configuration tests actually represent a form of static analysis, as they don’t execute source code during the process of their execution, even though configuration tests are executed as

pytestunit tests.

As we can see, the search of bugs has the least significant role in this list and everything else is available when using free open source tools.

Which of these static analysis types should be used in your project? Sure, the more the better! What is important here is a proper implementation, which will be discussed further.

A Delivery Pipeline As a Multistage Filter and Static Analysis As Its First Stage

A pipeline with a flow of changes (starting from changes of the source code to delivery in production) is a classic metaphor of continuous integration. The standard sequence of stages of this pipeline looks as follows:

-

Static analysis

-

Compilation

-

Unit tests

-

Integration tests

-

UI tests

-

Manual verification

Changes rejected at the N-th stage of the pipeline are not passed on stage N+1.

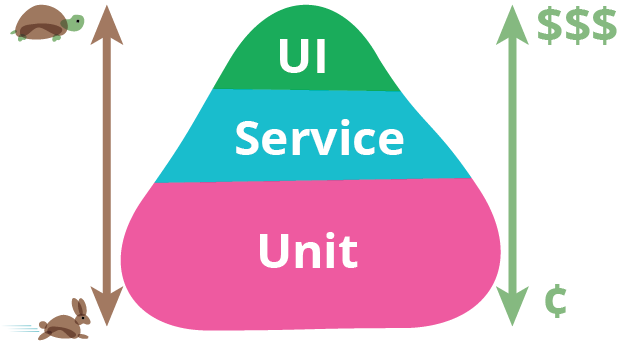

Why so and not otherwise? In the part of the pipeline which deals with testing, testers recognize the well-known test pyramid:

At the bottom of this pyramid, there are tests that are easier to write, which are executed faster and don’t tend to produce false positives. Therefore, there should be more of them, they should cover most of the code, and should be executed first. At the top of the pyramid, the situation is quite the opposite, so the number of integration and UI tests should be reduced to the necessary minimum. People in this chain are the most expensive, slow, and unreliable resource, so they are located at the very end and do the work only if the previous steps haven’t detected any defects. In the parts not related to testing, the pipeline is built by the same principles!

I’d like to suggest the analogy in the form of a multistage system of water filtration. Dirty water (changes with defects) is supplied in the input, and as the output we need to get clean water, which won’t contain all unwanted contaminations.

As you may know, purification filters are designed so that each subsequent stage is able to remove contaminant particles of smaller size. Input stages of rough purification have greater throughput and lower cost. In our analogy, it means that input quality gates have greater performance, require less effort to launch, and have less operating costs. The role of static analysis, which (as we now understand) is able to weed out only the most serious defects, is the role of the sump filter as the first stage of the multi-stage purifiers.

Static analysis doesn’t improve the quality of the final product by itself, the same as the sump doesn’t make the water potable. Yet in conjunction with other pipeline elements, its importance is obvious. Even though in a multistage filter the output stages potentially can remove everything the input ones can, we’re aware of consequences that will follow when attempting to get by only with stages of fine purification, without input stages.

The purpose of the sump is to offload subsequent stages from the capture of very rough defects. For example, a person performing code review should not be distracted by incorrectly formatted code and code standards violation (like redundant parentheses or branching nested too deeply). Bugs like NPE should be caught by the unit tests, but if before that the analyzer indicates that a bug is to appear inevitably — this will significantly accelerate its fixing.

I suppose it is now clear why static analysis doesn’t improve the quality of the product when applied occasionally, and must be applied continuously to filter changes with serious defects. The question of whether the application of a static analyzer improves the quality of your product is roughly equivalent to the question, "If we take water from dirty ponds, will its drinking quality be improved when we pass it through a colander?"

Introduction in a Legacy Project

An important practical issue: how do we implement static analysis in the continuous integration process as a quality gate? In the case of automated tests, it is clear: there is a set of tests, and a failure of any of them is a sufficient reason to believe that a build hasn’t passed a quality gate. An attempt to set a gate in the same way by the results of static analysis fails: there are too many analysis warnings on legacy code, you don’t want to ignore them all. On the other hand, it’s impossible to stop the product delivery just because there are analyzer warnings in it.

For any project, the analyzer issues a great number of warnings being applied in the first time. The majority of warnings have nothing to do with the the proper functioning of the product. It will be impossible to fix all of them and many of them don’t have to be fixed at all. In the end, we know that our product actually works even before the introduction of static analysis!

As a result, many developers confine themselves to the occasional usage of static analysis or using it only in the informative mode which involves getting an analyzer report when building a project. This is equivalent to the absence of any analysis, because if we already have many warnings, the emergence of another one (however serious) remains unnoticed when changing the code.

Here are the known ways of quality gates introduction:

-

Setting the limit of the total number of warnings or the number of warnings, divided by the number of lines of code. It works poorly, as such a gate lets changes with new defects through until their limit is exceeded.

-

Marking of all of the old warnings in the code as ignored in a certain moment and build failure when new warnings appear. Such functionality can be provided by PVS-Studio and some other tools, for example, Codacy. I haven’t happened to work with PVS-Studio. As for my experience with Codacy, their main problem is that the distinction of an old and a new error is a complicated and not always working algorithm, especially if files change considerably or get renamed. To my knowledge, Codacy could overlook new warnings in a pull request and at the same time impede a pull request due to warnings, not related to changes in the code of this PR.

-

In my opinion, the most effective solution is the racheting method described in the "Continuous Delivery" book. The basic idea is that the number of static analysis warnings is a property of each release and only such changes are allowed, which don’t increase the total number of warnings.

Ratchet

It works in the following way:

-

In the initial phase, an entry about a number of warnings found by the code analyzers is added in the release metadata. Thus, when building the main branch, not just "release 7.0.2" is written in your repository manager, but "release 7.0.2, containing 100,500 checkstyle-warnings. If you are using advanced repositories manager (such as JFrog Artifactory), it’s easy to keep such metadata about your release.

-

When building, each pull request compares the number of resulting warnings with their number in a current release. If a PR leads to a growth of this number, the code does not pass quality gate on static analysis. If the number of warnings is reduced or not changed — then it passes.

-

During the next release, the recalculated number will be written in the metadata again.

Thus, slowly but surely, the number of warnings decrease to zero. Of course, the system can be fooled by introducing a new warning and correcting someone else’s. This is normal, because in the long run, it gives the same result: warnings get fixed, usually not one by one, but by groups of a certain type, and all easily-resolved warnings are resolved fairly quickly.

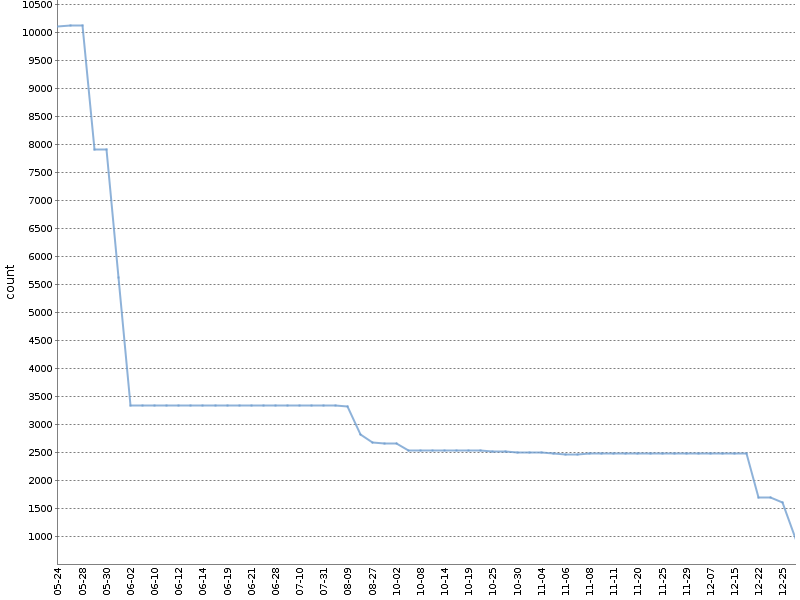

This graph shows the total number of Checkstyle warnings for six months of such a ratchet on the one of our open source projects. The number of warnings has been considerably reduced, and it happened naturally, in parallel with the development of the product!

I apply the modified version of this method. I count the warnings separately for different project modules and analysis tools. The YAML file with metadata about the build, which is formed in doing so, looks as follows:

celesta-sql:

checkstyle: 434

spotbugs: 45

celesta-core:

checkstyle: 206

spotbugs: 13

celesta-maven-plugin:

checkstyle: 19

spotbugs: 0

celesta-unit:

checkstyle: 0

spotbugs: 0In any advanced CI-system a ratchet can be implemented for any static analysis tools, without relying on plugins and third-party tools. Each of the analyzers issues its report in a simple text or XML format, which will be easily analyzed. The only thing to do after, is to write the needed logic in a CI-script. You can peek and see https://github.com/CourseOrchestra/2bass/blob/dev/Jenkinsfilephere] or here how it is implemented in our source projects based on Jenkins and Artifactory. Both examples depend on the library ratchetlib: method countWarnings() in the usual way counts XML tags in files generated by Checkstyle and Spotbugs, and compareWarningMaps() implements that very ratchet, throwing an error in case, if the number of warnings in any of the categories is increasing.

An interesting way of ratchet implementation is possible for analyzing spelling of comments, text literals and documentation using aspell. As you may know, when checking the spelling, not all words unknown to the standard dictionary are incorrect, and they can be added to the custom dictionary. If you make a custom dictionary a part of the source code project, then the quality gate for spelling can be formulated as follows: running aspell with standard and custom dictionary should not find any spelling mistakes.

The Importance of Fixing the Analyzer Version

In conclusion, it is necessary to note the following: whichever way you choose to introduce the analysis in your delivery pipeline, the analyzer version must be fixed. If you let the analyzer update itself spontaneously, then when building another pull request, new defects may emerge, which don’t relate to changed code, but to the fact that the new analyzer is simply able to detect more defects. This will break your process of pull request verification. The analyzer upgrade must be a conscious action. Anyway, rigid version fixation of each build component is a general requirement and a subject for a another topic.

Conclusions

-

Static analysis will not find bugs and will not improve the quality of your product as a result of a single run. Only its continuous running in the process of delivery will produce a positive effect.

-

Bug hunting is not the main analysis objective at all. The vast majority of useful features is available in open source tools.

-

Introduce quality gates by the results of static analysis on the first stage of the delivery pipeline, using the ratchet for legacy code.